Having given you John Swinney’s take on the GERS figures (Government Expenditure & Revenue Scotland), here is Craig Dalzell‘s considerably more in-depth analysis from Commonweal. We’ve added the images here. They didn’t appear in his article.

If things go back to normal next year…

Welcome to the second year of the Covid Discontinuity. As I noted last year, we’re in the middle of the worst possible thing that can happen to a statistician – a major event that throws out all of the carefully plotted trends and predictions. Last year I also used the phrase dreaded of every economic seer or scryer – “If things go back to normal next year…”

Well, they didn’t. Covid continued despite the best efforts of politicians in Scotland and the UK to ignore it, Brexit bit harder, the economic turmoil blamed on the escalating war in Ukraine caused a major fuel crisis that threatens to harm millions in the UK, inflation and interest rate spikes combined with continued wage repression raise the very real threat of a second Winter of Discontent and around Europe and the UK will be hosting Eurovision despite only coming second place.

“Deficit” has decreased from last year’s exceptional level …

In purely budgetary terms, things do seem to be improving somewhat as the Covid support money slows down or stops completely (Don’t look at the ongoing pandemic, lost work and productivity due to illness or future increased health spending though…also don’t look at the massive looming catastrophe as cuts to social care are causing the NHS in England to grind to a halt and may be responsible for around 500 deaths a week in England alone…). The notional Scottish “deficit” is £23.7 billion – still higher than the pre-Covid trend of around £15 billion but down from last year’s exceptional £36.5 billion.

Part of the reason for the decrease in the deficit is, of course, the economy switching back on again after Covid and generating tax revenue again. Acting Finance Minister John Swinney touted this as “the largest revenue increase on record” but really it’s just the tax revenue returning to pre-Covid trends after a downwards blip. It reminds me of the time that Yanis Varoufakis pointed out that if you destroy a country’s economy to the point that its GDP is zero, then any subsequent growth would be “record GDP growth”. The same thing is happening here.

This jump in revenue (about £7.8 billion since last year) only partially explains the drop in deficit though. The rest has come from a £1 billion drop in public expenditure since last year. In fairness to the Scottish Government, public expenditure by devolved Government has increased by about £2.3 billion but this has not been enough to compensate for the £3.3 billion cut in spending “in and for Scotland” controlled by the UK Government. The bulk of this cut is, of course, in direct economic support (such as Covid furlough) and cuts to social protection (like withdrawing the Universal Credit uplift). Other notable parts of the UK’s reserved expenditure “for” Scotland is the £2.5 billion rise in national interest debt payments. Whenever someone says that Scotland “couldn’t afford” spending in Scotland we have to ask what powers an independent Scotland would lack that an independent UK is using on “our behalf”. We also have to ask why the UK is charging Scotland these interest payments at all when it itself has already sequestered that debt within the accounts of the Bank of England and is thus paying interest effectively to itself.

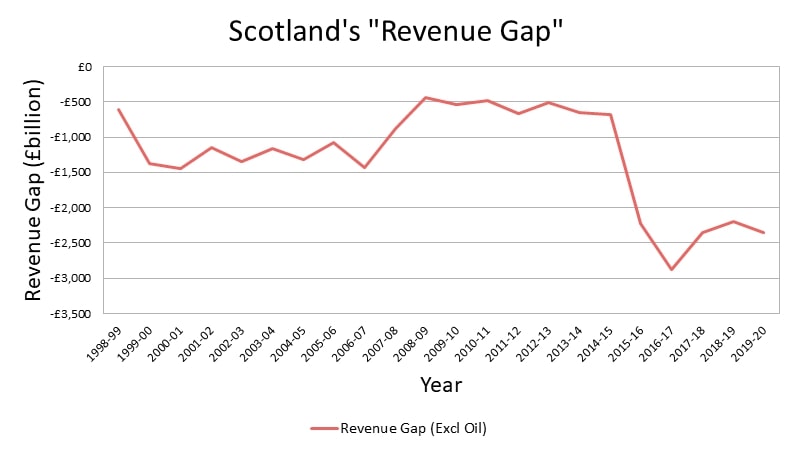

Revenue Gap

The relative “Revenue Gap” that Scotland experiences as a member of the UK is still prominent. This is the gap between the revenue that Scotland gets in taxation and the revenue that we would get if we were assigned a “population share” of the UK’s total tax revenue. If we look only at onshore revenue, that gap now stands at a record breaking £6.5 billion – three times what it was at the time of the 2014 indyref.

The largest competent of this gap is a £3.7 billion shortfall in income tax due to generally lower wages in Scotland for similar jobs and the structure of the UK economy that encourages the concentration of senior positions in London and the South East. We can test this hypothesis by noting that Scotland actually bring in more than our population share of VAT (to the tune of about £138 million) which suggests that per capita consumer spending is slightly higher in Scotland than in the UK as a whole. This is the “marginal propensity to spend” at work. Folk who need to spend money to live, spend it. Folk who have already met their basic needs tend to save that money thus contribute less to the economy as a percentage of their total income. If you earn ten times as much as I do, you might buy more or nicer things than I do, but you’re not as likely to spend ten times as much on them.

Scotland continues also to bring in less in Council Tax and Buildings Transactions Taxes as a result of our lower house prices (despite increases and lack of supply becoming major stress points in some parts of the country) and we see continued reductions in our “share” of taxes on unearned income such as Capital Gains while on the other side Scotland still brings in more than our “share” in alcohol and tobacco taxes despite a levelling off in the growth of both. These two taxes are a significant marker of the wellbeing of a nation and Scotland’s relatively high consumption of both as well as the devastating impact of other (illegal and thus untaxed) drugs has been directly linked to decades of deprivation and social breakdown caused by the deliberate political actions of the UK Government.

Levelling Up?

But of course, the UK is supposed to be “Levelling Up” the nations and regions outwith London, isn’t it? This was a major manifesto promise of the Johnson Government but, by its own metrics, it has not only failed but has been actively counter to that goal and has acted to concentrate even more of the UK’s wealth into the tax haven that is the capital. When anyone responds to this year’s GERS report by mentioning a “Union Dividend” then what they actually mean is that Scotland’s economy is being actively and deliberately repressed but that we receive a handout – controlled by those doing the repression – in compensation and that the advocate of the Dividend actively supports this.

What Scotland can do…

First and foremost, we need our independence so that we can properly restructure our economy into something that actually benefits both us and the planet. Before then, we need to do more to make our society bearable in the face of the UK’s economic failures. If I could have the ear of the Scottish Government now I’d call for a few policies to be enacted immediately. First, we need to fix the housing sector. An emergency rent freeze which would later give way to rent controls and tenants rights and a massive acceleration in the programme to retrofit houses. Every house we bring up to passive energy standards is a house that frees its occupant from fuel poverty permanently.

We also need to bring in new sources of tax revenue to stop Scotland’s wealth being sucked out of the country. This must include better land and property taxation along with comprehensive land reform.

And third (but not finally, there’s far more to talk about than I can fit into this column, this week) we need to improve Scotland’s investment landscape. We’re still seeing our natural capital being sold off for a pittance by the Scottish Government. That must end. It is with no grim pleasure that I see the First Minister now telling people that the reason we can’t have a National Energy Company is because her now abandoned plan to create one would have failed for precisely the reason that we told her and her Government that plan would fail back in 2017. Instead of just another retail energy company, we need an actual, asset-owning energy company (see here for how those assets could be nationalised for no greater cost to you than it would be to leave them in the private sector) along with strategic development of Scottish energy assets via a Scottish Energy Development Agency. The bottleneck is Scotland’s limited borrowing power. The Scottish National Investment Bank is slowly winding through the path to get that power but it is not going fast enough and the Scottish Government is not pushing the UK Government hard enough to get it. Do that, and everything else becomes almost as easy to do as it would be if we were an independent country.

In conclusion…

GERS will continue as it always has done and if you notice the similarities between this analysis and previous ones by me then that’s because the same arguments are continuing as well. It’s clear now that the UK’s economy is broken perhaps beyond repair but it’s also clear that GERS cannot be the be-all-and-end-all of Scotland’s economic analysis either – certainly not the analysis of how Scotland would perform as an independent country based on its current performance as a “region” of a deeply unequal United Kingdom.

Common Weal continues to advocate for a better kind of economy for Scotland. We’re still waiting on those who hold GERS up as a sign of Scotland’s inevitable failure to do the same.

(Published by Commonweal 25 August 2022: Analysis: GERS 2021-22. For more information about the Revenue Gap see here)